It used to be all the rage to photograph in excruciating detail the “unboxing” of a new piece of gear, especially hardware that few people (or no one else) yet had. Unboxing was great, but it’s sort of like a wedding or a birth: The actual event is relatively brief, and the really important stuff comes afterwards, as you spend years together.

Likewise, unboxing a new Macintosh may be exciting, especially if it’s a surprise. But the important part comes next. While Apple includes quite a bit of software, and offers more for free download via the Mac App Store, what else should a new user or a fresh system get?

As a nearly 30-year veteran of Mac ownership, I have 10 solid suggestions that will make your life better by shaving off the little irritations that remain in Mac OS X 10.10 Yosemite and in Apple’s bundled software. A new Mac user will be happier than otherwise, and a veteran user looking to refresh a system will find the time and effort savings quite rewarding as well.

LaunchBar

While OS X’s Launchpad and Spotlight can, in different ways, let you quickly find and open apps, documents, and other things, they can be maddening. Launchpad’s interface is hardly useful when you have more than a handful of apps, and Spotlight searches everything, rather than specific categories and in specific ways. Instead, pick LaunchBar ($29 individual, $48 family), which indexes and links to all sorts of stuff: music, contacts, apps, emoji, search history, bookmarks, and more.

LaunchBar can be invoked from a keystroke—I use the default Command-Escape. Then you just type a few letters to select the thing you want, and press Return to launch it or open it with the appropriate app. LaunchBar’s bar, however, also lets you perform most Finder actions with a Command-shortcut and carry out calculations.

LaunchBar can also add Clipboard depth, turning into something like the old pre-OS X Scrapbook: You can revert to and cycle through previous items you’ve copied or cut.

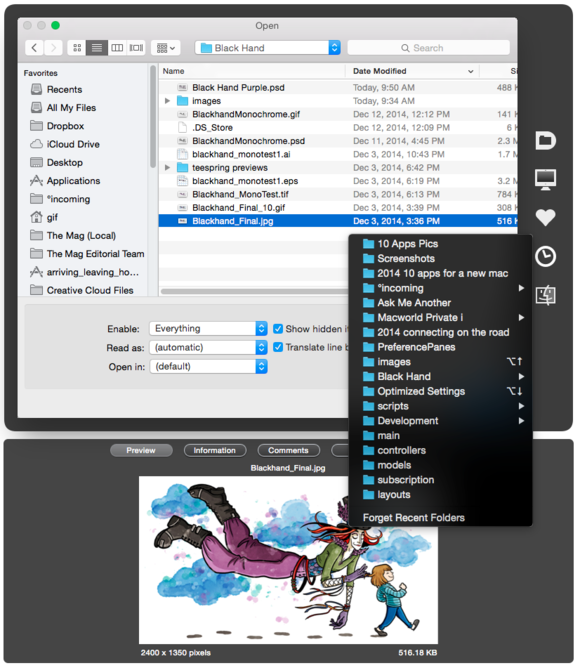

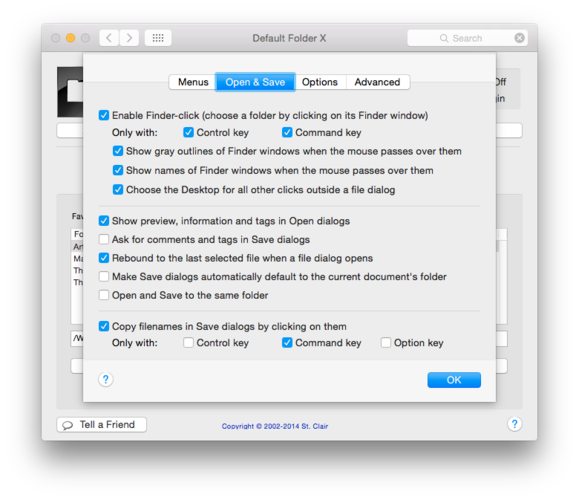

Default Folder

There are three elements of Yosemite itself that I spend more time interacting with than any other: the Open dialog, the Save dialog (and variants like Export), and Finder window navigation. Default Folder ($35) enhances all of these to your advantage in efficiency and organization.

When installed, the app wraps your open and save dialogs in a bunch of extra interface items. On one side, you can select from volumes and special locations, Finder windows, favorited locations, and recently visited folders. The file-navigation dialogs can also be set to snap to the last document opened or other locations, while pressing Option plus the down or up arrow cycles backward or forward through recent folders. Another item allows a variety of Finder-style file actions directly within the dialog, like rename, duplicate, and move to trash.

A pane at the bottom reveals a preview, Spotlight comments, tags, and permissions, as well as file data like creation date and whether the item is locked or not. There’s a host of other options, too: Tap a key combination, and the current folder is opened in the Finder. With Default Folder installed, you never have to painstakingly navigate your drives and folders.

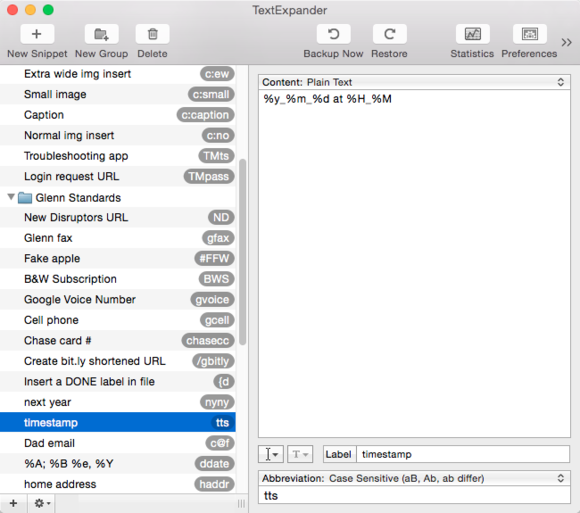

TextExpander

I know this is crazy talk, but what if you could replace the tedious repetitive typing of common phrases with a few keystrokes? Such shortcutting dates back decades—once known as “macroinstruction expansion” or “macros”—and TextExpander ($35 individual, $45 family) is the modern mature version of it.

Start with figuring out a few characters to type instead of your name or mailing address. Advance to using its tools for tapping a few keys to insert the current date, formatting it as you like. Move to employing prefabricated AppleScript to tap into URL shorteners, handling the roundtrip from clipboard to a tiny path. Graduate to its fill-in forms, which allow you to compose a message with selectable fill-in values to automate replies.

Smile revised its iOS version, TextExpander Touch ($5) to work within the add-on keyboard approach in iOS 8. Snippets can sync using Dropbox among Mac and iOS devices.

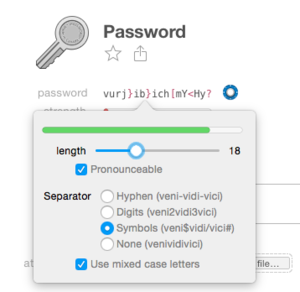

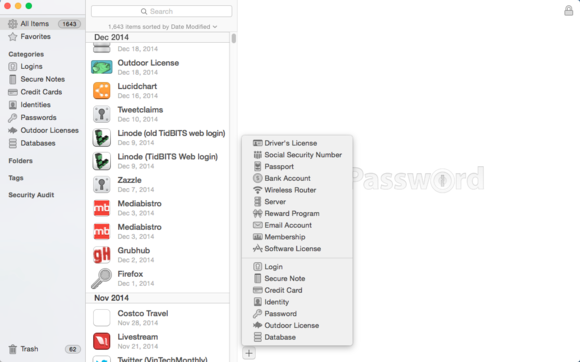

1Password

Security pundits, including yours truly, recommend that you create a unique strong password for every site or service you use. That’s impossible for a human to manage, but an integrated password generator and secure storage app like 1Password ($50) handles that with ease. It can create random password according to rules you set, or those absurd ones imposed by sites, and then securely store them for you.

That would be perfectly dandy, but not terribly useful if that’s all it did. However, 1Password also comes with browser plug-ins for Safari, Chrome, and Firefox, which let you invoke the app while visiting a site. Tap a keystroke, and it either prefills a username, password, and more, if there’s only one match; or lets you choose among multiple accounts for a site. When creating an account, the password generator can be invoked in the same way.

1Password also stores and can fill in one or more identities (address information), as well as credit-card details. Versions are available for Windows, iOS, and Android, and a password database can be synced among them. (The App Store version is required for iCloud sync with OS X and iOS.)

The similarly featured LastPass is an alternative for those who want to be able to gain access to passwords via website, which 1Password doesn’t offer.

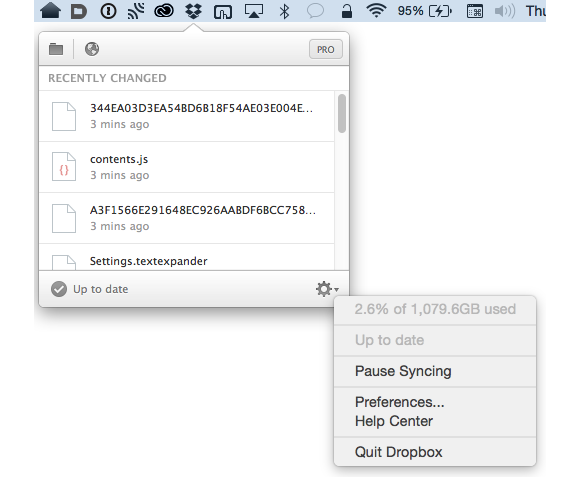

Dropbox

Keeping files up to date among multiple computers was a pain for many years. It wasn’t until Dropbox (free tier with 2 GB to 16 GB; 1 TB Dropbox Pro, $10/month or $100/year) appeared—a harbinger of cloud storage—that it became simple. Dropbox has a single folder into which you can place anything, and it’s copied to its Internet storage in your account, while also synchronized to any computer logged into the same account. (You can selectively omit specific subfolders on each machine.)

That would be enough, but Dropbox also offers two kinds of sharing. Shared folders sync the contents to any members who have joined the folder. A shared link allows any recipient to download a file or folder, or browse a folder’s contents.

Because Dropbox keeps a copy centrally, it keeps track of every change. Older versions and even deleted files are available for up to 30 days after a change or removal, and a $39-per-year upgrade to Dropbox Pro, called Extended Version History, extends that to a year. Dropbox’s iOS client lets you browse its cloud-stored versions, forward files, and download them to the app or open in other apps.

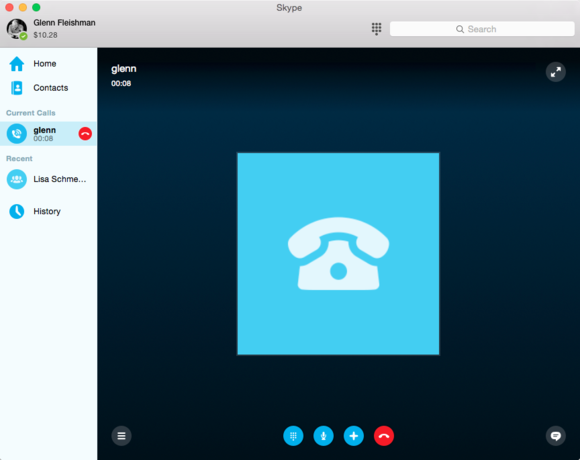

Skype

You already have FaceTime available on your computer and iOS devices. Why would you need Skype (free)? Because not everyone you know has a Mac, iPhone, or iPad, and because FaceTime doesn’t come with a calling plan, even though in Yosemite, OS X can access your iPhone to make and receive calls to landlines and cellular numbers.

Skype has a tattered history of Mac updates, but it remains the lingua franca for person-to-person and group Internet telephone calls. The service also has inexpensive calling plans for making unlimited phone calls to specific countries (such as the US and Canada), and cheap per-minute rates without a plan or to countries not included in a plan. You can pay for one or more incoming “real” phone numbers, too, placing them in countries in which you routinely receive calls, making it a local call for residents there.

It offers audio only and video calls, as well as screen sharing, file transfer, and instant messaging, along with SMS. I’ve used Skype for years as my main incoming and outgoing business line to avoid the fixed cost, and as it’s typically higher quality than a cell call.

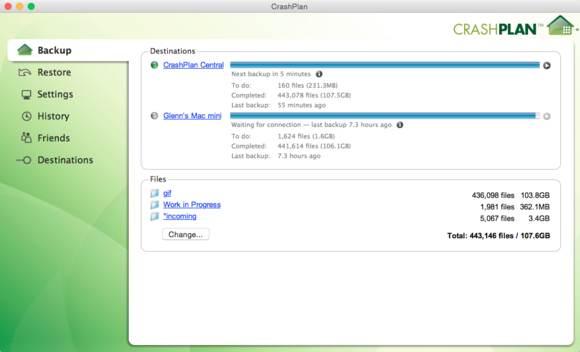

CrashPlan

CrashPlan can back up any selection of files to a locally connected drive, a local-area network volume, a peer’s drive elsewhere, or its cloud service—in any combination. Only the cloud storage comes with a fee attached, $4-$6/month individual, $9-$14/month family. The family subscription option lets you pull in any of your otherwise backup-adverse relatives without them having to manage the details of a separate account themselves.

The peer-to-peer option lets you push your encrypted files to someone else’s drive anywhere on the Internet. That other person gives you a code, and off your files go onto their backup volume or a separate volume you could provide, offering true offsite backup without a recurring fee.

CrashPlan isn’t a full-system clone. For that, Time Machine or Super Duper ($28) is a better option. Rather, CrashPlan is best at archiving your documents, preferences, and applications, and can store endless revisions of the same files for recovering older drafts.

I have about 1.5TB stored with CrashPlan’s cloud service across my own and several family computers, and have relied on restoring files from the cloud and local drives many times, both through its Mac interface (including over 600GB after a recent drive failure) and its iOS app.

CrashPlan’s major downside is that it continues to require Java, an extra installation in OS X for years. Installing Java for CrashPlan is safe, because it’s not enabled for use on the Web without extra steps. Still, if that’s a stumbling block, Backblaze (unlimited storage, $4–$5/month per computer) comes highly recommended by many colleagues.

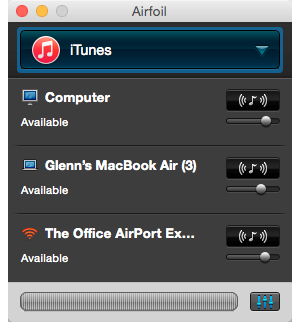

Airfoil

AirPlay is one of the best things about Apple’s ecosystem of audiovisual-friendly devices, and many strictly audio devices support AirPlay audio playback, too, including a Yamaha receiver I purchased a couple of years ago. But AirPlay has a number of limits. iTunes is the only Apple software that has a specific AirPlay option, which includes simultaneous playback to multiple devices. Otherwise, you’re limited to choosing a single device from Sound preferences to which to shunt all system audio.

Airfoil ($25) works around this limit by letting you take just the audio output of any software or audio input device and route it to one or more AirPlay-compatible receivers, including an Apple TV or AirPort Express. Better still, Rogue Amoeba offers Airfoil Speakers apps, free software for receiving Airfoil audio for Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, and Linux.

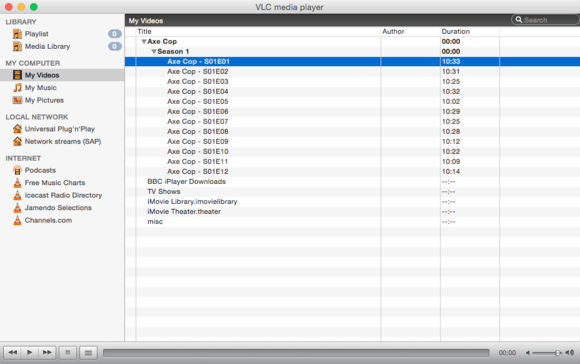

VLC

VLC (free) is the Swiss Army knife of video playback software. QuickTime Player can handle popular formats in a straightforward way, but everything it can’t, VLC can. VLC can play Internet streaming video of all sorts, read various disc formats, and convert some files it can’t read. If you deal with older file formats, say, those used by people that eschew H.264 because of patent issues, or video created or distributed for Windows and Unix variants, VLC is a one-stop shop.

Beyond video file support, VLC can open and convert tons of audio formats, which you might find in sorting through several decades of cruft on the Internet and in your own digital history, depending on your age. It can also directly open YouTube URLs, subscribe to podcasts, make video playlists, and play Internet radio stations from a large, built-in list.

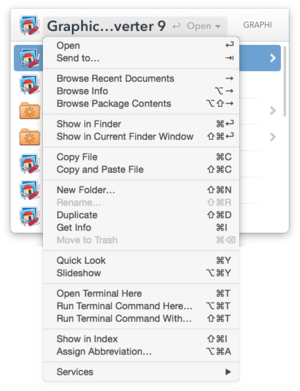

GraphicConverter

As VLC is to video (and audio) formats, GraphicConverter ($40) is to image files. While Apple’s Preview offers a decent subset of image viewing and manipulation controls, GraphicConverter has more in common with Photoshop without the subscription fee now required for Adobe’s graphical-editing pioneer, nor nearly as steep a learning curve.

GraphicConverter can open just about anything, offers photographic (non-linear levels) and image-editing (gradients, fills, and like) tools, and the basics like cropping, canvas resizing, and up- and downsampling. I often turn to GraphicConverter’s Browse command to view images in a directory, where I can preview and see file data, as well as rename or delete them.

You can directly import images from scanners and cameras (including in RAW format), and GraphicConverter can upload directly to Google+, Flickr, and other services. And if you need to process a number of images—converting a folder from TIFF to JPEG, for instance—the program has simple batch processing, with more advanced options available to those who need them.

No comments:

Post a Comment